The Mummy (1932)

The best horror films aren’t merely scary, although that is an undeniable part of the equation. They also bother with engaging plots, believable characters, understandable themes, and a sense of style. Consider The Phantom of the Opera, which not only embraced the melodrama of the original novel but also enveloped you with its grandiose gothic sets. Or The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, with its psychological twists and turns. Or Dracula, in which Bela Lugosi posed dramatically in the shadows, creating a visceral sense of dread. Or Frankenstein, in which an element of pathos made the monster sympathetic, in turn creating a different kind of horror – the horror of watching helplessly as a misunderstood soul is shunned by the very people he wished to connect with.

Although not without some technical merits, The Mummy doesn’t have the extra spark of any of the films mentioned above. It’s the horror equivalent of light entertainment – purely superficial, obviously capitalizing on the 1922 excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb in Egypt, lacking the elements that plow through through our rational defenses and stimulate the deeper, darker areas of the imagination where we believe, deny it though we may, that something as terrible as what we’re looking at on the screen could actually happen to us. It doesn’t even try that hard to be scary. It’s a silly film, which, given the innate fantasy of supernatural horror stories, is really saying something.

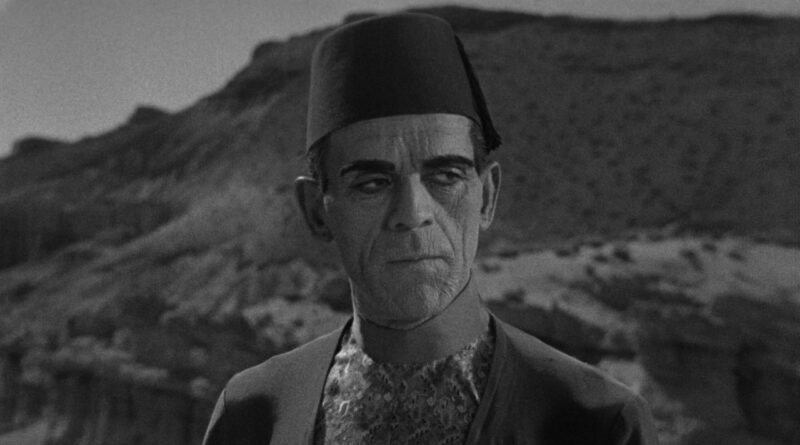

Boris Karloff, who convincingly brought Frankenstein’s Monster to pathetic life, plays the title character as artificially as a world’s-fair automaton. With deeply wizened makeup effects that bury his expressions, lines of dialogue that are both unnaturally stilted and overly expository, and a voice kept more or less as natural as his own, neither Karloff nor the filmmakers go to great lengths to allow for an emotional connection between character and audience. Only when we see something of ourselves in these characters, however awful they may be, can we truly be terrified by them. I can muster praise for individual closeup shots of Karloff looking directly into the camera, his sunken, circled eyes illuminated to the extent that his stare is unnervingly piercing.

The story begins with a 1921 Egyptian excavation, where an assistant unwisely reads the hieroglyphics off an unearthed scroll and revives an ancient mummy from his sarcophagus. The mummy escapes by merely shuffling away. Prior to the reanimation, the excavation’s leader (Arthur Byron) and his colleague (Edward Van Sloan) deduce that the mummy had been buried alive without his organs removed, presumably as payback for a sacrilege. Flash forward ten years; the mummy, an ancient prince who inexplicably masquerades as a modern-day Egyptian that speaks flawless English (Karloff), has somehow masterminded the excavation of a female mummy with the devious intention of bringing her back to life.

Preposterous as this already is, the filmmakers up the ante by throwing in an instantaneous romance between a half-Egyptian socialite (Zita Johann) and the son of the original excavation leader (David Manners), the socialite repeatedly being hypnotized by the mummy’s light-drenched gaze, and the implication that the socialite is the reincarnation of the woman the mummy fell in love with thousands of years ago. I’m willing to overlook any preposterous storytelling, so long as the filmmakers work to get me involved with the story. In the case of this film, the story is told so quickly (the film runs just seventy-three minutes) and with such disregard for detail and character development that I simply couldn’t suspend disbelief.

Perhaps I’d be more forgiving had the film had a better sense of style. Setting aside the makeup effects and some of the lighting techniques, we don’t get the sense that the filmmakers were going the extra mile to make the film look good. The sets, from the modern-day furnished rooms to the ancient chambers of stone and sand, are cramped and minimally dressed. The special effects, most notably a vat of liquid from which the mummy is able to summon images of the past, look cheaply produced. If this is a case of the budget being too tight for elaborate sets or convincing effects, the filmmakers could have compensated with better dialogue and more engaging performances. Alas, The Mummy didn’t go that route. What a disappointment.