Footloose (1984)

I think the issue with Footloose is that the filmmakers labor under the delusion that the material should be taken seriously. Sadly, the idea of a small town banning dancing and rock music is innately ridiculous. Perhaps if director Herbert Ross had loosened up a bit, if he had just allowed the story to be the fantasy that it so clearly is, it might have been a great deal of fun. There were times when I could see flashes of greatness, most notably during the dance sequences, which brimmed with energetic choreography and infectious music. Granted, dance sequences don’t require plot or character development; they exist for no reason other than for the sheer spectacle of it. If that’s the best a movie can offer, if it truly can’t be anything more than an hour-and-forty-minute music video, maybe it shouldn’t aim for something more.

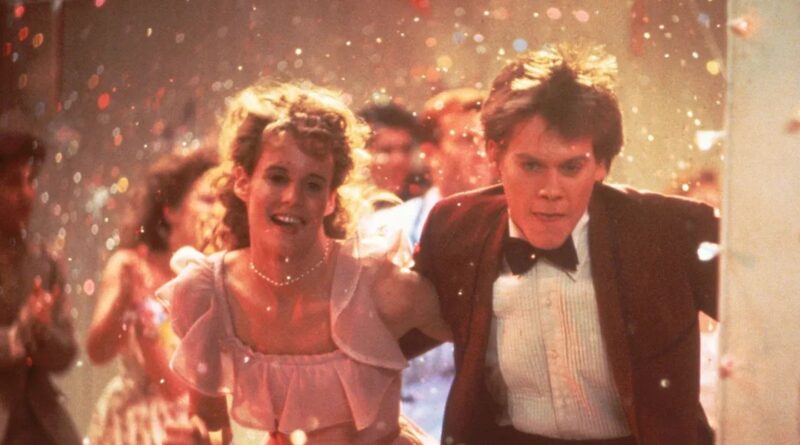

As it is, the film is implausible, contrived, and at times wildly inconsistent in tone. It’s populated by characters that have virtually no gray areas of development, being either too broad or too narrow. At the latter end of the spectrum is Ren McCormack (Kevin Bacon), a high-schooler who has just moved with his mother (Francis Lee McCain) from urban Chicago to Bomont, a small, rural Midwestern hamlet where everyone knows everyone else. Since a car accident claimed the life of several teenagers some years earlier, the city council imposed a strict ban on rock music and dancing. Ren spends the entire film either shooting his mouth off or breaking the law. All eventually leads to a town hall meeting, where he will plead his case for an abolishment of the anti-dancing law. It’s hinted that his rebellion stems from abandonment issues with his father, although the filmmakers don’t pause long enough to develop this any further.

At the former end of the spectrum is just about every one of the secondary characters. This would include Ren’s friend Willard (Christopher Penn), who spends most of his screen time hanging around Ren like a pathetic little puppy dog. At times, mostly when he laughs, he literally seems like the kid who just wants someone to play with but is too afraid to ask. After Ren drives him and a duo of girls across the state line so that they can experience dancing and music at a local bar, Willard reluctantly admits that he can’t dance. This paves the way for a later scene, specifically a dance-training montage that’s hilariously, and unintentionally, homoerotic. It probably didn’t help that the song playing during the sequence was Deniece Williams’ “Let’s Hear It For the Boy.”

A pivotal character is the Reverend Shaw Moore (John Lithgow), who’s not only the local preacher but also the town’s moral authority. For reasons not made entirely clear until it’s too late for us to care, he spearheaded the movement to ban rock music and dancing. He spends most of the film being so close-minded that his eventual turnaround seems to come completely out of the blue. You might even call it miraculous. How is it possible that in one scene you’re sermonizing from the pulpit about the loose morality of rock music and in the next you’re letting the teens go off to a last-minute prom? This man is not at all easy to define, which isn’t to suggest that he’s complex or ambiguous. I think this is simply an example of bad character development, a flaw that stems directly from the screenplay by Dean Pitchford. Perhaps he should stick to the song lyrics that made him famous.

All stories like this require a love interest. Here enters the Reverend’s rebellious teenage daughter Ariel (Lori Singer); she begins as the wild girlfriend of the high school bully, appropriately named Chuck (Jim Youngs), but soon enough finds her way into the arms of Ren. Something might have developed here had their relationship not been founded on tiresome cliches, most notably how overprotected and misunderstood she is by her father. Alas, their being together is merely a piece of the machinery, which operates in full view of the audience. If you can’t see where the story is leading within the first ten minutes, you’re probably not paying attention.

The only real decent scene the movie has to offer is the final dance, and even then I’m forced to question the likelihood of it going the way it does. If these kids have not danced in a number of years, then why is it that most of them move with the energy and grace of professional choreographers? You’d think they would be just as clueless about what to do as Willard was. The upside is that watching them dance is a thoroughly enjoyable experience. Credit also to the music producers and songwriters that contributed a number of fun songs to the soundtrack. Thanks to them, we have Bonnie Tyler’s “Holding Out for a Hero,” Shalamar’s “Dancing in the Sheets,” and of course, the title song by Kenny Loggins. Unfortunately, not even great music could have saved Footloose from its story, characters, or direction.